Introduction

Every reader’s experience of a book is affected by various elements, including its presentation (cover illustration, the paper, the font used), its provenance (where it came from) and the age and circumstance of the reader when they first read it. Even so, the primary stuff of a book is the language used in it, the style and the words. Books featuring the Belgian detective Hercule Poirot are written in two languages, English with a smattering of French; given that most of her readers are children or adults who don’t speak French, I thought it was time to examine how it is used and whether it adds to the experience of the books. In doing so I uncovered one novel in which the French used is crucial to the understanding of what is happening.

Poirot-french examples

In most of the Poirot stories, Agatha Christie uses a variety of simple French exclamations and expressions to establish the detective as a person who thinks in a different language to everyone else. A dictionary of “Poirot-french” would be limited in the main to a few hundred phrases, pleasantries and, especially, exclamations. The latter are such as might have been used by ‘un bon catholique’ such as Poirot at the end of the 19th Century (around the time when a very young Agatha Christie learned to speak French). Here are three very typical examples of ‘Poirot-french’:

Parbleu!

Nom d’un nom d’un nom!

Sapristi!

Interjections such as these are repeated throughout the 33 novels and 50-plus short stories that feature Hercule Poirot, writen between 1916-1969. They are toned-down versions of exhortations to le bon Dieu. English equivalents might be ‘Good Lord’, ‘Great Scott!’ and so on (in the Granada TV adaptations of these stories, these exclamations, in their English translations, are also routinely made by Captain Hastings, who never uses them in the books.)

Simple stuff

As readers work through the Poirot oeuvre, those with even the most limited understanding of French to start with will begin to recognise his French expressions as old friends. They may have to decide for themselves what they actually mean (and not just Anglophone readers – these books have been published in over 100 different languages).

Phrases in French are presented in italics to make them stand out (and easy to skip past). Most people would probably consider them to be simple embellishment, indications that Poirot is amazed / annoyed / pleased, as the case may be, rather than crucial to the stories.

In one book, however, there is a bit more to it than that: a reader skipping past the italics will miss a few elements that make it one of the better Christie novels.

Not so simple stuff

That story is ‘Death on the Nile’. Written in 1937, the Poirot-french used by Agatha Christie in it is a bit more varied than usual, especially when Poirot is muttering to himself. She includes an obscure proverb, an old Belgian poem and other utterances that give us a nudge as to Poirot’s thought-processes, and even pointers as to what is actually going on, that are not given elsewhere in the English text.

Rather than ‘skipping past the italics’, a reader hoping to solve this puzzle would be advised to try and work out what Poirot is saying. When I read the book for the first time, at the age of 11, I delighted in these French bits and memorised most of them, even if own translations were somewhat wide of the mark. It all seemed to add to the fun.

Death on the Nile

The story’s setting is a river cruise up the Nile, and, just as in the other transport-driven Poirot books from the 1930s (Murder on the Orient Express and Death in the Clouds), the SS Karnak has a wide range of nationalities on board: as well as the Egyptian crew, there are French, German, American, Italian, English and (of course!) Belgian passengers. With one notable exception, none of them are thrown when Poirot switches from one language to another, and that is a hint in itself.

The plot of Death on the Nile is a classic Christie love-triangle-with-a-twist: Simon Doyle dumps his fiancée Jacqueline de Bellefort and marries her (rich) best friend, Linnet; Jackie stalks and threatens them on their honeymoon; Linnet is killed and Simon and Jackie are reconciled. Apparently… Further murders ensue amongst a complicated tangle of side-plots, including stolen jewels, trustee fraud and even an on-board terrorist.

Follow the French and you will be following the single strand that untangles the mystery.

The Use of French

Agatha Christie’s use of French is subtle. I have chosen 7 examples from the text (there is a full lexicon of all the French used in this book at the bottom of this blog).

1 Empressement

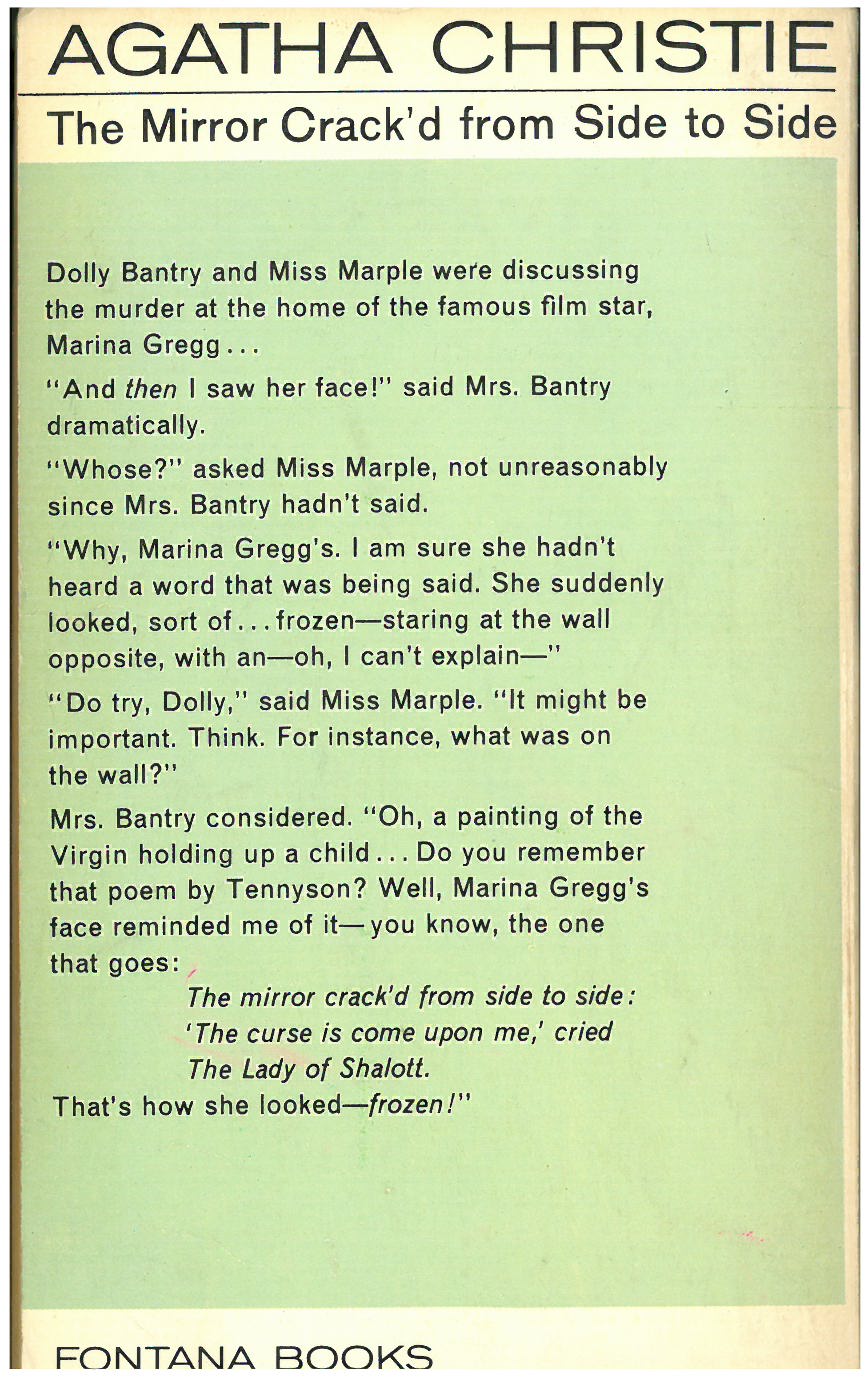

Here is an example from Chapter 1, when Poirot appears for the first time and is shown to his table at Chez Ma Tante (all the illustrations are taken from the 1977 Fontana edition). Although Poirot doesn’t say the word, he is clearly thinking it.

Empressement is not an easy word to guess. When I first came across it, aged 11, I thought of the nearest word to it in English, so my translation of empressement was ‘being impressed by someone’. It actually means ‘alacrity, eagerness’, but, although they are not the same thing, the meaning of the sentence is not radically changed by inserting my version: Blondin clearly is impressed by Poirot and will always find a table for him.

Agatha Christie could have used “alacrity” but chose not to. Empressement is not a word that is in common use in English. By using this one word she creates an effect whereby the reader is watching the events of the whole of this pivotal scene through Poirot’s eyes, rather than observing him in action, as we do for the rest of the book.

2 Une qui aime…

We are still in the restaurant with Poirot as he sees Simon and Jackie for the first time, dancing, and hears them discussing their honeymoon in Egypt. He makes a crucial observation:

Whenever one is allowed access to Poirot’s inner thoughts, and it does not happen often, then one had better pay attention; his first impression of character is never shown later to be misplaced in any of the books in which he features.

The meaning of the phrase in italics here is not that difficult to work out, presuming you can guess what the verb aimer means and that une is the feminine form of ‘one’ and un the masculine. Nor do you need to know the reflexive verb se laisser; Poirot’s echoing of Jackie’s “I wonder…” tells you what it must more or less mean.

If you skip the italics, however, you will be missing a hint about the driving element of the relationship between Simon and Jackie, the two main protagonists: one who loves, and one who is content to be loved.

Tiens! C’est drôle

In Chapter 6, Poirot repeats the same phrase when he first actually meets Simon, on holiday in Egypt. By the time of that meeting, Simon has married Linnet instead, and they are on their honeymoon. They are being stalked by Jackie, and Simon has just declared that he would like to “wring the little devil’s neck”:

Now, Poirot had just spoken with Jackie, and she had used word-for-word the same simile as Simon does about the moon and the sun. So Poirot’s reaction when he hears these words again minutes later – loosely translated: “Hullo, that’s a bit funny!” – should make an alert reader sit up and store this hint away for later: Simon was supposed to be avoiding Jackie. The use of the word drôle, which has an almost exact English equivalent, makes the phrase quite easy to decipher. Even so, Simon does not understand it and Poirot avoids translating it for him.

It is Simon’s stupidity and simplicity that is also hinted at here: for a start, he is seemingly the only character in the book who hasn’t a clue what Poirot is saying when he lapses into French! Jackie had already told Poirot that Simon was “a very simple person”.

Later on, recalling these conversations, Poirot realises that Jackie had from the start been training Simon in exactly what to say and do, to avoid his giving the game away with his gormless comments. Unfortunately for her, she failed.

Nom d’un nom d’un nom!

Another hint at the presence of stupidity-in-action is given in Chapter 13, when Poirot and the doctor examine the crime scene.

“Nom d’un nom d’un nom!” is one of Poirot’s strongest exclamations, and he uses it on many occasions, usually when confronted by something that stretches his credulity to its limit (as here).

The usual French phrase would have been ‘nom d’un nom’: ‘in the name of God’, a euphemism for nom de Dieu. With three noms*, you could translate it as ‘What in the name of God and heaven is this nonsense-!’

*In the Granada TV version of Death on the Nile, David Suchet, clearly enjoying himself, is heard to stretch it to four…

C’est de l’enfantillage

This extract is taken from the same scene.

The stem enfant of the word enfantillage should make the meaning of Poirot’s comment pretty obvious: ‘This is sheer childishness’.

His suggestion of childishness, rather than ‘melodrama’, is a huge hint as to the identity of the perpetrator. There are many melodramatic characters on board the Karnak – Mrs Otterbourne, Richetti, Jackie herself – but the only one simple, or childish, enough to believe that it might be possible, for someone who has been shot point blank in the head, to dip her finger into the wound and write the accusatory letter J on the wall, is Simon.

On ne prends pas les mouches avec le vinaigre

In chapter 22, Poirot and Race make a further search of the same cabin.

Poirot is examining two bottles of nail varnish, one full and one empty. His reaction after sniffing them made little sense to me when first I read it: “You don’t put vinegar on your moustaches” was my ill-informed guess. The actual translation is “You don’t catch flies with vinegar”, but even that does not tell us much.

What I think he is saying is that Linnet presumably used make-up to make herself look attractive to herself and others but she would hardly have been applying something that had should have such a bitter smell.

He has no intention of explaining himself to Race. The rest of his reply seems to indicate that there are no clues to be found. Poirot usually scorns the idea of crawling around looking for clues such as cigar ash, the absence of which here he appears to lament. His use of the French proverb indicates that he has found something far more significant – that there is a residue of something red and acrid-smelling in the bottle that was not there originally – and also that he wishes to keep it to himself.

La vie est vaine

In Chapter 24, Poirot is once again alone with Jackie.

They meet just after the discovery of Louise Bourget’s body. Poirot quotes to her the whole of a poem by the Belgian writer Leon de Montenaeken (d 1905). When I first read it I thought Poirot had made it up!

The French is very simple but not easy to render into English. Here is my attempt (the notes at the end use a more literal one):

Life is a play

We love and we hate …

And then it’s good-day

Life is so slight

We hope and we dream …

And then it’s good-night

It is not immediately obvious what the relevance of the poem is here. It is like a funeral oration, so it could be in reference to Linnet, who has lived and loved, but has died suddenly while still young. The context in which it is placed, however, prompts a different reading.

In the lead-up to the poem, Poirot once again recalls Jackie’s sun and moon simile, the thing that had first aroused his suspicion of her. He looks at Jackie “half-mockingly”, because by now he does not believe a word of what she says, and “half with some other sentiment” because he is genuinely sad about her likely fate.

Later, on the same page, Poirot tells Race that he knew for sure what had been happening when they found Louise Bourget. The words of the poem, recited just afterwards, could equally apply just as well to Jackie as Linnet, because Poirot by now suspects that she will also die young (by capital punishment). As it turns out, his sympathy for her allows her to take her own way out.

Mesdames et Messieurs

The French used by Poirot in Death on the Nile contains hints about the workings of his mind during the investigation which he does not express in English or make clear to the others until it has finished. For the rest of the book, he openly discusses (in English) all the other twists such as the stolen pearls, the Italian terrorist and the crooked trustee, but the reader who ‘skips past the italics’ might miss out on these hints:

- That Jackie is totally besotted by Simon and will do anything for him; he’s quite happy to be taken in hand (une qui aime et un qui se laisse aimer)

- That Jackie had trained Simon in what to say and do even though he was supposedly not speaking to her (tiens! c’est drôle, ça)

- That a child-like simpleton murdered Linnet in her cabin (c’est de l’enfantillage) – Jackie had already told him that Simon was “simple”…

- That the strange red substance in the nail varnish bottle (‘on ne prends pas les mouches avec le vinaigre’) is an important (if obscure) clue as to how the murder was contrived

Poirot’s use of French can be divided into three groups – exclamations, pleasantries and obscure commentary. It does not take a genius to understand most of the phrases that comprise the first two groups, but in Death on the Nile readers need to also attend to his murmurings if they are going to have a decent chance of working out whodunit.

Death on the Nile Dictionary

Here is a list of all the expressions in French used by Hercule Poirot in Death on the Nile.

À merveille!: ‘Excellent’; usually used by Poirot as an adverb (i.e. ‘we proceed à merveille’)

À votre santé: ‘Your good health’ (Poirot toasts the Otterbournes, one of whom is a dipsomaniac)

Ah, non!: ‘No way!’ Reaction to Bessner after the discovery of Linnet’s body

Ah, vraiment! ‘Indeed!’ Poirot is suspicious of Pennington’s motives

article de luxe: ‘Luxury article’ – in reference to Jackie’s pistol

Bien: ‘Ok, good, fine’ (variously)

bon Dieu!: ‘Good God’

Bonne nuit: ‘Goodnight’

Cache: ‘Hiding-place’ (for Mrs Otterbourne’s booze)

Ce cher Woolworth: ‘Dear old Woolworths’ – Poirot considers a cheap handkerchief

C’est de l’enfantillage!: ‘This is sheer childishness!’ Still musing on the letter J scrawled in blood on the cabin wall.

C’est vrai: ‘That is true’. To Race

Cette pauvre petite Rosalie: ‘That poor young girl.’ He also refers to ‘cette pauvre Madame Doyle’ but it is Rosalie Otterbourne that he feels sorry for.

Écoutez, madame: ‘Now listen, madame…’ The beginning of a long speech to Linnet.

Eh bien… : ‘Well….’

empressement: ‘Eagerness, alacrity.’ Poirot observes the maître d’ finding him the best table

en verité: ‘In truth’

femme de chambre: ‘chamber-maid’

jeune fille: ‘young girl’

la politesse: ‘politeness, courtesy’

le roi est mort – vive le roi!: ‘The king is dead, long live the king’: referring to Linnet. Joanne Southwood had previously (and more accurately) referred to her as “la Reine Linette”.

les chiffons d’aujourd’hui: ‘today’s chiffons’: the expression ‘causer chiffons’ used to mean to gossip about clothes; Rosalie and Jackie have been comparing lipsticks, which Poirot sees as its modern equivalent.

Ma foi!: ‘Indeed!’ This is followed by “madame, that was close” when the boulder narrowly misses Linnet. The nearest literal translation to this would be the old-fashioned “i’ faith”

Mais oui, Madame: ‘Indeed it is, madame’ (to Mrs Allerton, when she proclaims the lovely night)

Mais c’est tout: ‘But that’s all’

Moi, qui vous parle: ‘I, I am telling you’ – Poirot being emphatic to Race.

mon ami: ‘my friend’ (to Race). An endearment often addressed to Hastings in other books

Mon cher Colonel: ‘My dear Colonel’ (Race again)

Mon Dieu!: ‘My God!’ When Simon complains that Jackie isn’t being reasonable

Mon enfant: ‘my child’ – addressed to Jackie (not Simon!) when he tries to give her advice

Nom d’un nom d’un nom!: ‘In the name of God and all the saints in heaven!’ Poirot sensibility is outraged by the J scrawled in blood on the cabin wall.

On ne prends pas les mouches avec le vinaigre: ‘You don’t catch flies with vinegar’. Poirot finds something suspicious in the nail-varnish bottle. An English version of this is “you catch more flies with honey than vinegar”.

Parbleu!: ‘Heavens above’ – followed by “but I am not the diving seal!” To Mrs Allerton

Précisément: ‘Precisely, exactly’. Used by Poirot a great deal in all his stories

Peut-être: ‘Perhaps’. To Colonel Race

Quel pays sauvage: ‘What a wild country…’ to Race

Qu’est-ce qu’il y a?: ‘What is it?’ In response to an exclamation from Race.

Sacré: ‘Damn!’ Unusually strong language for Poirot. The French translator Marie-Josée Lacube changes it to “Enfin!” in her version of “Poirot Investigates”.

Tenez!: ‘Now look here!’ (to Rosalie Otterbourne, who has been fiercely criticising Linnet)

Tiens, c’est drôle, ça: ‘Hello, that’s a bit funny’… when Simon unwittingly lets a clue slip

Très bien, Madame: ‘Very well’ (to Mrs van Schuyler)

Une qui aime et un qui se laisse aimer: ‘One who loves and one who lets himself be loved’

Zut!: ‘Blast!’ Poirot fails to find the necklace

La vie est vaine

La vie est vaine La vie est brêve

Un peu d’amour Un peu d’espoir

Un peu d’haine Un peu de rêve

Et puis bonjour Et puis bonsoir

Life is vain Life is short

A bit of love A bit of hope

A bit of hate A bit of dream

And then good-day And then good-night

%201.6.jpg)

%201.8.jpg)