There is no hint whatsoever of racism, sexism or any other kind of prejudice in the narrative of these novels, although characters are allowed to express their own bigotries, often exposing themselves as they did so.

What leaps to the eye in these stories are the characters’ concerns about immigration and inter-marriage, and the many casual put-downs by men when discussing the opposite sex.

A MURDER IS ANNOUNCED 1950

Refugees who arrived in Britain during WW2 feature in a few stories from the 1950s. Not everyone shows hospitable reactions to them, but Letitia Blacklock at least tries to understand her servant Mitzi, who fled persecution in Central Europe.

Please don’t be too prejudiced against the poor thing because she’s a liar. I do really believe that, like so many liars, there is a real substratum of truth behind her lies. I mean that though, to take an instance, her atrocity stories have grown and grown until every kind of unpleasant story that has ever appeared in print has happened to her or her relations personally, she did have a bad shock initially and did see one, at least, of her relations killed. I think a lot of these displaced persons feel, perhaps justly, that their claim to our notice and sympathy lies in their atrocity value and so they exaggerate and invent.

THEY CAME TO BAGHDAD 1951

The stories set in the Middle East often contrast the locals with their colonising counterparts, not always in the latter’s favour (Agatha Christie would have loved just to sit there without being expected to say anything):

Captain Crosbie often looked pleased with himself. He was that kind of man… Nothing remarkable about him. There are heaps of Crosbies in the East.

‘Arabs find our Western impatience for doing things quickly extraordinarily hard to understand, and our habit of coming straight to the point in conversation strikes them as extremely ill-mannered. You should always sit around and offer general observations for about an hour – or if you prefer it you need not speak at all.’

‘Rather odd if we did that in offices in London. One would waste a lot of time.’

‘Yes, but we’re back at the question: What is time? And what is waste?’

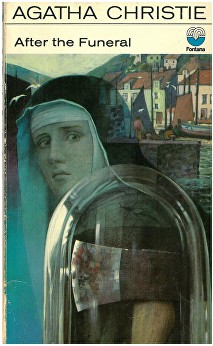

AFTER THE FUNERAL 1953

The faithful old retainer Lanscombe reflects on Cora’s marriage:

A Frenchman her husband had been, or nearly a Frenchman – and no good ever came of marrying one of them!

Poirot here is speaking for the author herself (as he often does):

‘Women are never kind,’ remarked Poirot. “Though they can sometimes be tender.”

HICKORY DICKORY DOCK 1955

‘Half the nurses in our hospitals seem to be black nowadays,’ said Miss Lemon doubtfully, ‘and I understand much pleasanter and more attentive than our English ones.’

Nurses had been invited from the Caribbean to bolster the new National Health Service. Later, Jean Tomlinson explains why she thinks Akibombo spoilt Elizabeth Johnson’s course work:

All these coloured people are very jealous of each other and very hysterical.’

On the other hand, here is Elizabeth Johnson talking about Sally Finch:

‘They are all the same, these Americans, nervous, apprehensive, suspecting every kind of foolish thing! Look at the fools they make of themselves with their witch-hunts, their hysterical spy mania, their obsession over Communism.’

This book was written at the time of the McCarthy witch-hunt of those suspected of ‘un-American activities’.

Finally, Mrs Nicoletis’ unique brand of man-management is to the fore as she upbraids her kitchen staff:

‘Liars and thieves,’ said Mrs Nicoletis, in a loud and triumphant voice. ‘All Italians are liars and thieves!’

DEAD MAN’S FOLLY 1956

The grateful Captain Warburton discusses his hostess:

‘But I believe she comes from the West Indies … One of the old families there – a creole, I don’t mean a half-caste. All very inter-married, I believe, on these islands. Accounts for the mental deficiency.’

Here is a brilliant put-down by Poirot of one of the cruder opinions prevalent at the time (and just before it):

Alec Legge remained serious. ‘I should like to see every feeble-minded person put out – right out! Don’t let them breed. If, for one generation, only the intelligent were allowed to breed, think what the result would be.’

‘A very large increase of patients in the psychiatric wards, perhaps,’ said Poirot dryly.

Here are two considered opinions about half of the human race (we can be reasonably certain that they were not shared by the author):

De Sousa shrugged his shoulders. ‘Ah, well! Why should one ask it of women – that they should be intelligent? It is not necessary.’

‘Women,’ said the Inspector sententiously, ‘tell a lot of lies. Always remember that, Hoskins.’ ‘Aah,’ said Constable Hoskins appreciatively.

… and men don’t? That should make a detective’s job easier.

4.50 FROM PADDINGTON 1957

Here is a typical slice of Agatha Christie: not her own opinion at all, but inserted (in the mouth of Dr Morris) to expose the wide-spread, somewhat ridiculous insularity of so many people at the time.

‘Ah well, I dare say he’d have lived to regret it if he had married a foreign wife.’

As an aside, doctors tend to get a hard time in her books: often the murderer, or talking rot.

ORDEAL BY INNOCENCE 1958

Yet another doctor is shown in a poor light:

‘She sounded – I can’t explain to you how she sounded.’

‘Irish blood,’ said MacMaster.

‘She sounded altogether stricken, terrified. Oh, I can’t explain it.’

‘Well, what do you expect?’ the doctor asked.

And here is yet another male dismissal of the female of the species – and once again it is the policeman in charge of the investigation:

She’s of the age when women go slightly off their rocker in one way or another.

CAT AMONG THE PIGEONS 1959

Cat Among the Pigeons finishes off the 1950s in a riot of prejudicial opinion.

“You think everyone you meet is dishonest.”

“Most of them are,” said Mrs Sutcliffe grimly.

“Not English people,” said the loyal Jennifer.

“That’s worse.” said her mother. “One doesn’t expect anything else from Arabs and foreigners, but in England one’s off guard and that makes it easier for dishonest people.”

This is not the author speaking, but the author once again mocking a particular dense English colonial type that she had no time for. Agatha Christie had a huge respect for the people of the Middle East, though maybe not the sheikhs:

“Oh well,” said Jennifer. “I expect the Queen often has to have people to lunch who don’t know how to behave – African chiefs and jockeys and sheikhs.”

“African chiefs have the most polished manners,” said her father.

Adam (appropriately enough, a gardener) keeps his boss informed of developments:

Her Highness arrived in style. Cadillac of squashed strawberry and pastel blue, with Wog Notable in native dress, fashion-plate-from-Paris wife, and junior edition of same (HRH).

‘Wog’ was in very common use in those days, especially among ‘colonials’, and could refer to just about any non-Caucasian. You never hear it uttered today (thank goodness).

His head gardener Briggs advises Adam about Italians …

“Now you be careful, my boy. Don’t you get mixed up with no Eye-ties. I know what I’m talking about. I knew Eye-ties, I did, in the first war …”

… whilst the investigating officer dismisses the French:

“Touchy,” said Bond. “All the French are touchy.”

Who can blame them? Or the Italians for that matter …