2017

Kenneth Branagh’s film version of Murder on the Orient Express will go on general release in November 2017. The previews have been available for a while. Branagh’s portrayal of Poirot, complete with luxurious moustaches, has already attracted a great deal of (not always complimentary) comment.

It is likely that he has chosen, deliberately, to distinguish himself as much as he could from previous manifestations of Poirot to make a role of his own. Having heard the voice he uses on the preview, I think he will succeed, as indeed did the two actors in the previous films of the book.

1974 and 2010

There have been two fine versions of the story already – one for the cinema, directed by Sidney Lumet in 1974, and one for ITV’s Poirot series (2010).

The film was was more or less faithful to the plot and the atmosphere of the book; it was a huge success (at the time the top-grossing British film ever) and is repeated often on TV. The ITV production team were keenly aware that their own efforts might be overshadowed by comparisons with it.

They set out to make a version that had a very different atmosphere, and in doing so created something that was more or less faithful to the original plot, but which questioned some of the attitudes and assumptions within it. It is very much a 2010 take on a book written in 1934.

What is interesting to me is that the actual story stands up incredibly well for itself in both cases. This blog will examine the differences between the two versions, and, in anticipation of the new film, speculate about what tricks it might have up its sleeve. But first, here is a resumé of the book’s plot and one aspect of the character of its main protagonist, Hercule Poirot.

Murder on the Orient Express – the original story

Hercule Poirot is recalled urgently to London from Istanbul and finds that the first-class carriage is fully booked. The director of the line, M Bouc, finds a bunk for him, to the consternation of most of the other passengers. One of them, named Ratchett, tries to hire his services en route, but Poirot turns him down because he (literally) doesn’t like the look of him.

During the night, the train is held up in a snow-drift as it makes its way to the Yugoslavian town of Brod. In the morning, Ratchett is found murdered in his cabin. It is clear that no-one could have entered or left the train, and that the killer must still be in the carriage. Ratchett had been stabbed twelve times.

Poirot is asked by Bouc to investigate and come up with a solution to present to the local police when they eventually get to Brod. He soon finds out that Ratchett’s real identity was that of the notorious gangster Cassetti, who had kidnapped and murdered the two-year-old Daisy Armstrong 5 years previously. Casseti had escaped conviction on a technicality, having used his connections to bribe the legal authorities.

There are twelve other passengers in the carriage, as well as the conductor. It soon becomes clear that every one of them has a connection with the Armstrong family, and that they had plotted this bloody revenge, in effect acting as judge and jury to effect it. The conspirators had gone to great pains to leave clues that threw suspicion on a supposed gangster associate of Cassetti. Unfortunately for them, the extreme weather conditions had rendered this alternative solution implausible, because he could not have got on or off the train as they had planned it.

Poirot, however, presents this solution, and the actual one, to M Bouc, and allows him to choose which one to present to the Yugoslavian police. M Bouc, in the interests of ‘natual justice’, but also in the interest of his line’s reputation, decides to present them with the evidence that points to a fugitive gangster.

Poirot retires from the case, and goes to his cabin to wrestle with his conscience.

The Justice of Hercule Poirot

Hercule Poirot describes himself as ‘un bon catholique‘ who ‘does not approve of murder’. He does not always seem to approve of the legal justice system either.

In many of his cases, he stops short of bringing the culprit to justice. He gives them instead the option of taking their own way out, presumably by committing suicide, although that word is never mentioned. He does so in order to spare them, or their loved ones, the horrors of what was inevitably to come: trial and the hangman’s rope. In one example, Poirot performs the execution himself.

The Murder on the Orient Express is the only example where he lets the killer(s) get away with it completely. This at odds with his often-expressed conviction that, once someone has allowed evil to enter into their heart, and committed murder – no matter what the provocation – they will probably do it again.

This possibility – that, having got away with it once, the conspirators might strike again – is ignored by the book and the 1974 film, but is very much present in the 2010 TV programme.

Murder on the Orient Express – the film

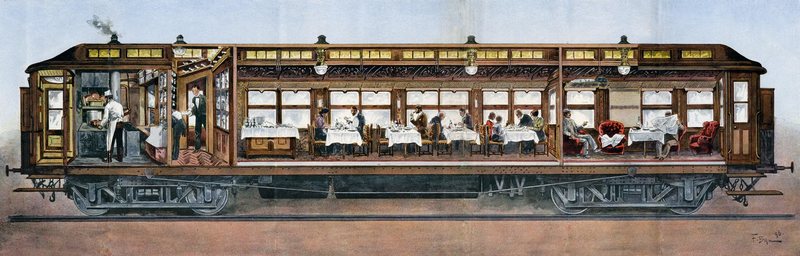

This film has an all-star cast, with many headlining actors seemingly content to play minor, almost stereotypical roles. The setting is luxurious, with the atrocious weather conditions outside seeming to have no effect on the comfort of the passengers and crew.

Albert Finney is a believable Poirot, even if a very young one (he was 38). He plays it for laughs quite a bit – in fact, most of the cast do. Jokes are added. Vanessa Redgrave, in the role of Mary Debenham, spends the whole film in a wry state of amusement at what is happening around her.

Albert Finney is a believable Poirot, even if a very young one (he was 38). He plays it for laughs quite a bit – in fact, most of the cast do. Jokes are added. Vanessa Redgrave, in the role of Mary Debenham, spends the whole film in a wry state of amusement at what is happening around her.

The star turn is undoubtedly Ingrid Bergman, as Greta Ohlsson, one-time nursemaid to the Armstrong household. She is only in one main scene, but absolutely fills the screen during it. It is a very moving performance of a simple woman who turned to religious devotion to help her cope with the aftermath of Daisy’s murder. The film was nominated for 6 Oscars but she was the only winner (for Best Supporting Actress).

The film follows the plot very closely, and when Poirot presents his two solutions and Bouc selects the false one, no-one seems bothered, least of all Poirot. The champagne is brought out and the killers all toast each other. The message is loud and clear: justice has been done, and twelve murderers are free to make their way home.

Agatha Christie was pleasantly surprised by the film (her last public appearance was at the premiére) because so many adaptations of her books had produced dreadful results. Even so, she did not like Albert Finney’s moustache: ‘I wrote that he had the finest moustache in England — and he didn’t in the film. I thought that a pity — why shouldn’t he?‘ Maybe that explains Branagh’s overblown affair…

Murder on the Orient Express – the TV programme

When I first saw the TV programme, I was disappointed. There was far too much emphasis on the supposed ethical dilemma that Poirot faced and religious elements obsessing both him and the other passengers on the train. Having re-watched it, I realise that I had missed the point.

Whilst not tampering with the books plot, the screenplay certainly tampered with its lenient attitude towards the conspiracy: it can never be justified that a group of people should elect themselves judge and jury and mete out their own version of justice.

To make that clear, Ratchett is transformed from a homicidal sadist to a God-fearing man hoping to atone for his crimes and seeking penance, and the righteous Colonel Arbuthnot has to be stopped from killing Poirot when it looks like he is about to betray them to the local police. In this version, Arbuthnot has allowed evil to enter into his heart.…

To hammer the point home further, the programme begins with the stoning to death of a woman by a mob in Istanbul, witnessed by Poirot, Arbuthnot and Mary Debenham. The victim was pregnant with another man’s child. The horrified onlookers are powerless to intervene, and Poirot says that it is best not to: the woman knew the rules, she knew what she was doing and she knew what would happen to her.

Similarly, Ratchett had also known what he was doing and is now all too aware of what probably lay in store. While he is being executed he is all too conscious, as the poor woman had been, of the first blows that are struck by those pursuing mob justice.

The focus of the rest of the film is on whether Poirot will allow them to get away with it. He does, just, but his logical mind tells him that they are no better than those casting the stones. Whether Arbuthnot and Debenham, who alone have witnessed both deaths, come to the same conclusion is doubtful.

Overall, this is a much darker version of the story (literally). As the train is held up in the snowdrift, its facilities and comforts become unavailable to the passengers. There is no running water and they are forced to sit in semi-darkness to await their fate. This is all a splendid contrast to the fun and frolics of the film, and there is no hint of self-congratulation at the end.

Overall, this is a much darker version of the story (literally). As the train is held up in the snowdrift, its facilities and comforts become unavailable to the passengers. There is no running water and they are forced to sit in semi-darkness to await their fate. This is all a splendid contrast to the fun and frolics of the film, and there is no hint of self-congratulation at the end.

Finally

The moral of the TV film reminds me of a wonderful passage from Tolkien:

There is no trace of pity for the victim in the book or the 1974 film (Agatha Christie would have been horrified if there was), but the audience might feel some when watching the TV film.

It will be interesting to see which version of the story Branagh’s will most resemble. Maybe he will produces something very different, with Poirot delivering the murderers to justice… My suspicion is that it will be a mix of the two – an all-star cast with an equivocal portrayal of the morality displayed by their characters.

Pingback: Poirot vs Count Andreyeni, the kick-boxing, ballet-dancing diplomat – SWIGATHA