THE BOOK Fontana, 1963 pp 254 1

A great Tom Adams cover, referencing the Tunisian dagger used in the murder and made memorable by the inclusion of the insect crawling up the dead man’s back. Insects would feature in many of his later covers. There is a daft and irrelevant spiel on the back – for a start, the “letter” precipitated the murder rather than coming afterwards.

ABOUT

Poirot has retired to King’s Abbott to grow vegetable marrows. He makes friends with his new neighbours by singular means, and soon becomes involved with them in a murder investigation. The book is narrated by one of the neighbours (Dr Sheppard).

This is the book with which Agatha Christie came of age as a crime novelist. It was also the one current at the time that she disappeared for 11 days, sparking off a manhunt that, bizarrely, involved Conan Doyle and Dorothy L Sayers (i.e. she was a major celebrity even then).

The solution to Ackroyd’s murder caused a sensation at the time, and its structure has continued to exercise the minds of academics and critics ever since.

CHARACTERS AND ATTITUDES

Possibly because this time the narrator is somewhat shrewder than the sometimes vacuous Hastings, the supporting cast is drawn with more care and humour than is often the case.

The different manifestations of the love between Roger Ackroyd and Mrs Ferrars, James and Caroline Sheppard, Miss Russell and Charles Kent, Ralph Paton and Ursula Bourne, Flora Ackroyd and Hector Blunt keep the plot moving, and enable the reader to overlook some of the absurdities of the how-dun-it–in-the-time-available.

The character of the narrator is far more complex and fully-formed than the Hastings that he replaces, and his sister is described with an obvious affection (she became the template for Miss Marple later).

Poirot is wonderfully and humorously drawn, starting with his inverted franglais (see below), leading to his assumption of command and increasing use of French expressions (all of which everyone involved is expected to understand), and ending with his anarchic solution: for the first but not the last time, Poirot uncovers the truth and keeps it from the authorities, meting out his own version of justice.

From then on during his career, Poirot’s attitude is quite often at odds with the justice system of the time, and not one you would immediately associate with un bon catholique.

Here is Poirot introducing himself to his new neighbour (having flung a vegetable marrow over the fence):

“I demand of you a thousand pardons, monsieur. I am without defence. For some months now I cultivate the marrows. This morning I suddenly enrage myself with these marrows. I send them to promenade themselves – alas, not only mentally but physically. I seize the biggest. I hurl him over the wall. Monsieur, I am ashamed. I prostrate myself.”

There is a gentle humour underpinning the plot. Here is a typical example:

Blunt said nothing for a minute or two. Then he looked away from Flora into the middle distance and observed to an adjacent tree trunk that it was about time he got back to Africa.

SWIGATHA RATING 9.9/10

Like many of her novels, this one is perhaps most famous for the ingenuity of its conclusion, but I think it is also among the best-written and funniest of all of them. It is not always appreciated how amusing Agatha Christie’s writing can be.

So, the book rates almost – as the Mah Jongg players might say in the Shanghai Club – as “Tin Ho”, the Perfect Winning: it nearly got a 10. Unfortunately, however brilliant the idea behind the plot is, I don’t think its timing works.

For example, the killer is invited by Roger Ackroyd in the morning to come to supper at 7:30pm. He decides to kill him that evening. His alibi will require him to tamper in his workshop with Ackroyd’s dictaphone so that it starts playing at a specific time, and get a stranger he meets in the afternoon to call him at home at another specific time – before he knows what time he will get the chance to be alone with his host.

WHAT HAPPENED NEXT

For Agatha Christie, along with the acquisition of global fame came the realisation came that, if she had to stick with Poirot, she could make him a much more rounded figure without Hastings around. The good Captain comes back every few years from the Argentine for the odd “hunt”, but some of her finest Poirot stories would have been impossible with him in tow.

Also, within a couple of years, Caroline Sheppard had been transformed into Miss Marple, with the publication of the first stories that would eventually be collected together as The Thirteen Problems.

WHAT HAPPENED ELSEWHERE

For the rest of the literary world, Ackroyd’s publication sparked a controversy about the fairness of its plot that raged for years. Among those contributing to the debate have been Roland Barthes, Edmund Wilson, Umberto Eco and Raymond Chandler, plus the Sorbonne Professor of Literature, Pierre Bayard.

In 1998, Bayard brought out a book called Qui a tué Roger Ackroyd? (which translates as Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?). It argued (and argued it almost undeniably well) that Poirot was suffering from delusions, that Sheppard was innocent and that his confession was to protect the real culprit, his beloved sister.

It might sound absurd that the minds of the great should be troubled by a whodunit plot twist, but a discussion about what readers can know, and what they have to fill in for themselves 2, is interesting in the context of any novel, and especially when it is narrated. 3

Edmund Wilson’s article for The New Yorker was entitled ‘Who cares who killed Roger Ackroyd?’ Evidently, many still do.

ADAPTATIONS

There was an appalling ITV adaptation in 2000 (written by Clive Exton) which reflected none of the charm or humour of the book. Worse, it changed possibly the most famous twist and ending of any detective novel, ever, replacing it with a fatuous bang-bang chase sequence. And yes, Caroline Sheppard is implicated in the murder. Maybe Exton had been reading Prof. Bayard.

There was also a Russian adaptation in 2002 Неудача Пуаро (which translates as Poirot’s Failure) that plays it pretty straight. The title comes from Sheppard’s Apologia:

A strange end to my manuscript. I meant it to be published some day as the history of one of Poirot’s failures!

NOTES

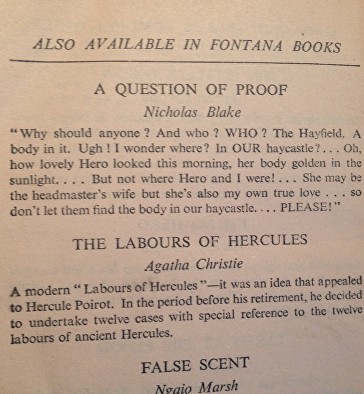

1 At the back of Fontana paperbacks of the time there was usually an Also available from Fontana section, which listed books of a similar genre with a short edited extract designed to intrigue the reader. The back pages of this book contained the following, bizarre, blurb:

Incredibly, ‘Nicholas Blake’ was the pseudonym of Cecil Day Lewis, the UK’s poet laureate at the time (and father of actor Daniel).

2 In the words of the great Russian author Vladimir Nabokov: ‘You don’t read a book, you re-read it.’

3 There is also a quite brilliant semi-spoof of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Gilbert Adair called The Act of Roger Murgatroyd. The twist at the end is up there with Agatha Christie’s.